The goal of this article is to explain two important use cases of the fourier transform, provide intuition for its value, and give a sense for how it works. The math and bare-parts breakdown of the fourier transform will be included in a future article.

Key Applications

Sampling

Imagine you have a device that records at every moment in time. It could be a microphone that records sound or a camera that records video. For every single moment in time, you would have either a sound bite (a sound recording at a momentary instant) or a video frame (a picture at a momentary instant. Videos can be thought of as a bunch of pictures shown in quick succession). Say this device recorded everyday 24/7. How would the recording/video be stored? Computers and storage devices have a finite amount of storage. A never-ending recording is a recording for an infinite amount of time and is an infinite amount of data. Further, since our perfect device records at every moment in time, there is also an infinite amount of data within a year, a month, or even just a day. Even within a second or a tenth of second, our perfect recording device has an infinite amount of data samples. For those unfamiliar, infinite is a construct, not a number, and there are different 'sizes' of infinite (some infinities are bigger than others).

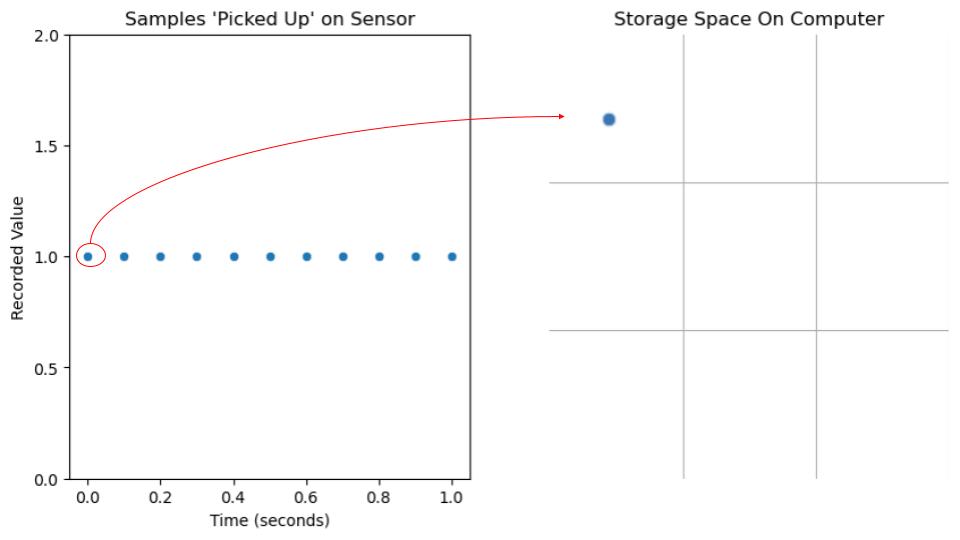

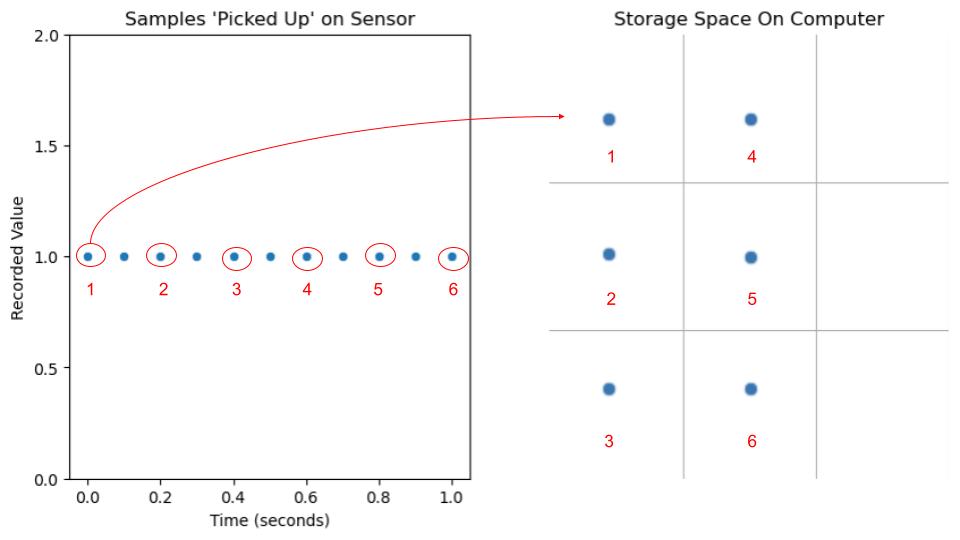

This 'perfect recording device' is just as unrealistic as a comptuter that can store an ever-lasting recording (or even a .1 second long recording with an infinite number of samples). However, since a computer should be able to store much more than just one song, the notion that we want to save less data than the recording device can record is still relevant. The solution to this problem is sampling.

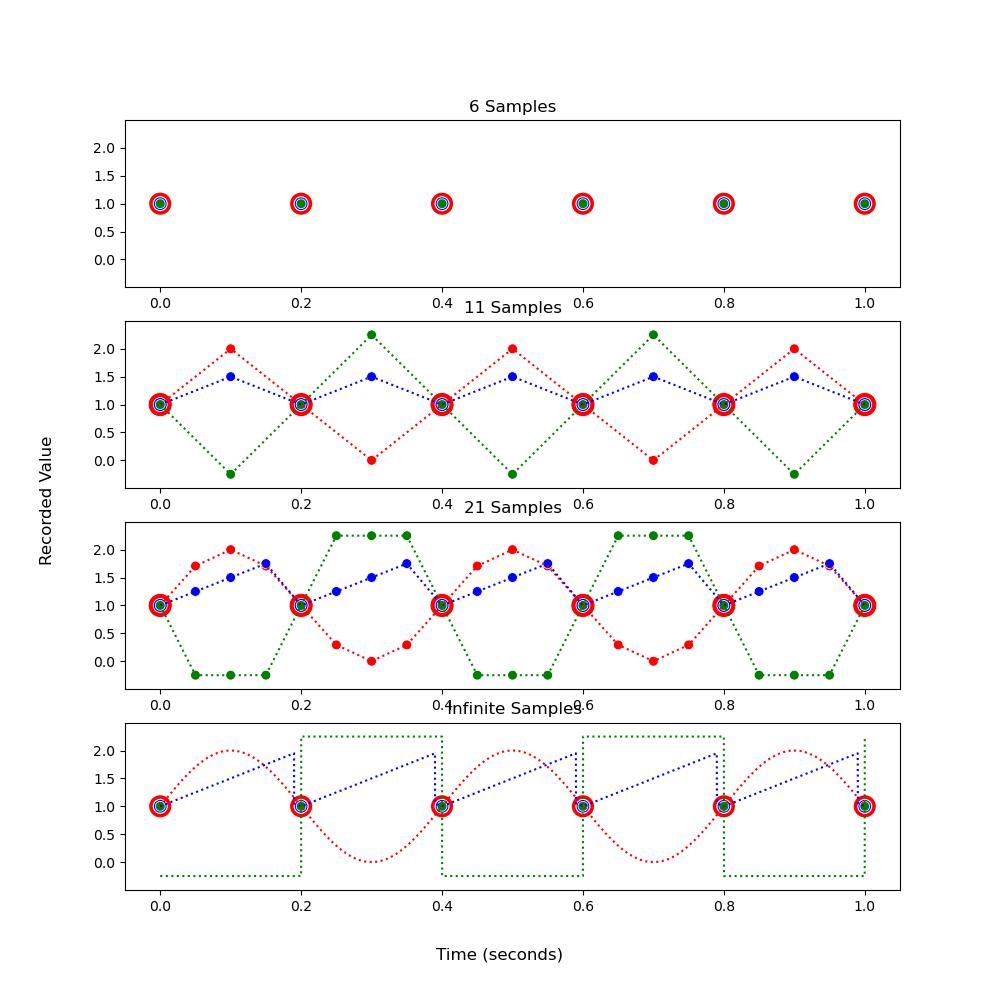

But what about a slightly more complex signal? 11 samples can represent a broad number of scenarios beyond just a straight line and as the number of saved samples are decreased in an effort to preserve memory, more and more initial signal shapes are possible (infinite samples = perfect encoding. As samples -> 0 more interpretations can be made from the encoding).

In order to save memory, we want to take as few samples as possible while still being able to determine the EXACT value of the signal at any time. But, from the last example, the samples required for this vary dramatically from signal to signal. This is what the fourier transform does in regards to sampling. The fourier transfor, allows for computers to determine how often to sample in order to efficiently 'know' the EXACT values of the signal.

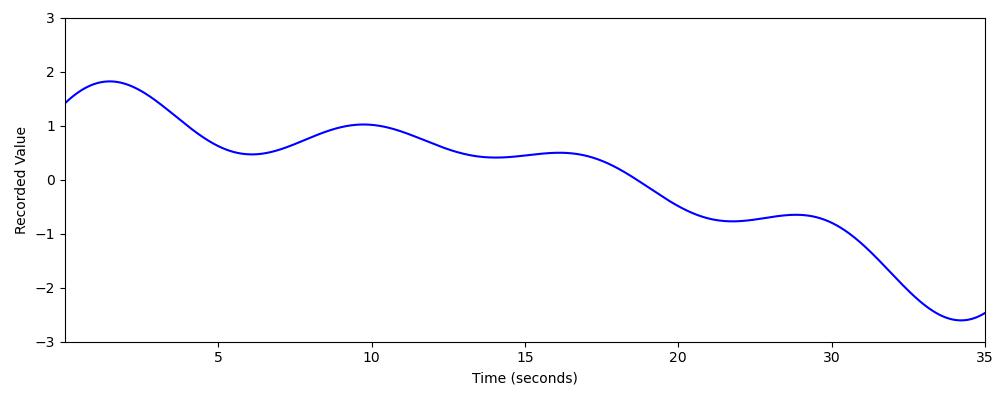

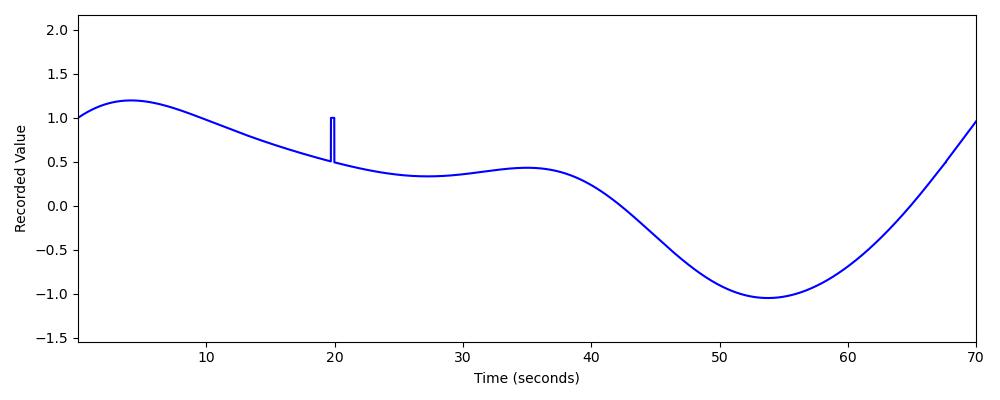

So far, all the signal examples shown have been relatively intuitive - They repeat after a certain amount of time and can be equated to fairly straighforward equations. What makes the fourier transform neat is that it can describe the value at any point of a signal even if the signal doesn't repeat or if the signal has weird features/bumps/sudden jumps without taking every single sample (taking a sample in the context of a computer means to know the sample value. Without knowing the value of each specific sample, the fourier transform can inform how often to sample in order to capture signal intricacies).

Hopefully I've done an adequate job at explaining the sampling problem and just how unintuitive a solution to this problem is. Here I'm going introduce another application of the fourier transform and in doing so, will explain the foundation for what it does to solve these challenges.

Filtering

Recorded values from a sensor are the sum of multiple inputs at each point in time. For example, ears/microphones at a concert might pick up on a singer singing, a person clapping, drums from the back of the stage, fans screaming, wind hitting the mic/ear, and the hum of air conditioning. Likewise, visuals from the eye or recorded as a video will 'see' the performance but will also capture flashing lights, stage fog, and the glare of a spotlight. The same applies for implanted biomedical devices and 5G cellular signals. Because 'a signal' refers to a measurment of some quantity that carries information, pretty much all electronics that communicate with another electronic has this multi-input property. In the case of a 5G signal, as the cellular signal bounces off buildings and the environment, phones recieve multiple versions of the same signal at slightly different times. Additionally, fog and humidity can distort/weaken cell signals and the internal electronics of a phone (such as wifi and bluetooth emitters) can create interfering signals that add to what is being recieved by the 5G signal reciever.

The challenge of removing unwanted aspects of a signal is just as relevent as the sampling problem. While sampling helps save information by lowering computation time and memory usage, filtering removes the unwanted aspects of a signal so that information can be decoded/interpreted as intended.

Special thanks to Dr. Joseph Young who taught me everything I know about the fourier transform.